This post is the text of the eulogy I gave at my mum’s funeral, and a poem chosen and read by my sister Cathy at mum’s burial. Mum was an incredible person and a wonderful, inspirational role model.

We love you mum and will miss you very much. Thank you for everything.

Judith Mary Martin

“Some people make things happen, some people watch things happen and some people wonder what happened” to paraphrase Jim Lovell, Apollo 13 astronaut.

Judith Mary Martin – whose life we celebrate today – unquestionably falls into the category of people who made things happen. Mum may not have flown to the moon, but she most certainly reached for the stars.

Born in 1934 in country Victoria, Judy had an older sister Faye, and a twin sister Joy. When still a little girl, her parents separated, and she moved with her mum and two sisters to Melbourne. It was the middle of the depression era: they lived in abject poverty, surviving on bread & dripping at times, doing midnight runners to avoid paying rent, and going to the pawnbrokers to get items out of hock when her mum – a factory worker – got paid. As a young girl, mum had already decided she would never work in a factory; she would get educated, work hard, and make sure that her family would have a stable and loving home life. She achieved all that and much more, despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles.

Having to leave school at grade 8 – aged 14 – wasn’t a great start. Mum’s first job was at the Imperial War Graves Commission, but she really wasn’t cut out for office work. She toyed with the idea of becoming a nun, but in the end chose nursing as her vocation. Once the decision was made, she then made it happen. Trouble was, nursing training couldn’t begin till she was 18, and mum was just 16. So she hounded the nursing director till she got a job as a probationer and then after significantly more hounding, she entered nursing training at the tender age of 17 years and 5 months. She was in her element, she loved the work, and she loved the girls she worked with. She said that those years were the best of her life, the most carefree, and loads of fun.

She worked hard, was determined to succeed, and eventually became Nurse Unit Manager (Charge Nurse) of the entire operating theatre department at a major Victorian Hospital. Although she left school at 14, she returned to study part-time aged 52, first to complete her VCE and then to graduate with a Bachelor of Nursing in 1992 aged 58; all the while working, and caring for her youngest children. She was still working two nights a week at the age of 72.

Life was anything but plain sailing. Two weeks after she started as a nursing probationer, her adored father died – he was 42 and she just 16; still a child.

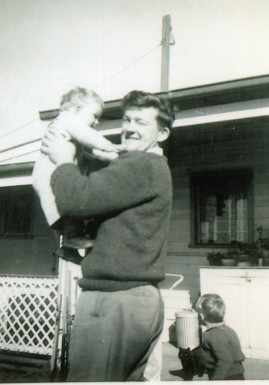

Mum married twice, had 10 children and 8 grandchildren. For much of the early years, there was very little money, and life was a constant struggle. By mum’s account, her first marriage was very unhappy and didn’t last long. In her second marriage, it was mum that mostly set the family goals, she who made things happen to achieve her aspirations. She orchestrated family moves upward, including from a “hovel” to a housing commission home (the “lap of luxury”) in country Victoria, by literally begging the local MP who she collared at a school function. She also triggered a later move by reporting the house we lived in to the local council, who swiftly condemned it as unfit to live in.

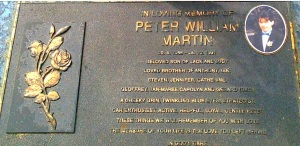

Meanwhile, there were personal misfortunes to contend with. As an infant, Geoff nearly died from an infection in the mid-60s. Later that same year, Dad was also in hospital for months after a terrible logging accident, leaving mum with a family of 6 kids and one on the way, with no income and no insurance. On Christmas Day 1979, a car ploughed through a red light into ours and mum and dad ended up in hospital for many weeks. Much, much worse though was the loss of two children: in 1973, mum’s 10th child Gerard died in childbirth. And in 1991, her 7th child Peter died aged 25, in a car accident. These tragic events nearly broke her heart. But as she said in her own words many years later:

“There are always things in life you wish you didn’t have to go through, because they hurt so much. But you know what? That’s part of the journey too.”

“Pick yourself up, dust yourself off and move forward.”

Mum did what she could, with the few resources she had, to improve the family’s lot: buying Lan Choo tea because it came with coupons to claim gifts in the store in town; getting her driver’s licence, and then helping teach many of her kids to drive – even if that did include falling asleep in the passenger seat with Steven at the wheel. In the 1970s, mum’s name was picked out of the barrel to spin the wheel on the Ernie Sigley Show. She won a TV, we think – and a trip to Sydney after Ernie found out she had so many children. Asked what message she wanted to send her family on national telly, mum famously said:

“I just hope someone remembers to make the school lunches”.

Perhaps it was the Ernie Sigley trip that started the travel bug: she began taking road trips with youngest children Jan and Cally – to the Great Ocean Road, Adelaide, Sydney. She took her first overseas trip when she was 47, with Cathy to visit Tony and Olga and grandson Eann in Israel and then on to Italy and the UK. Because she was going to be away such a long time, she left us a long list of things to do. Including a fire drill every evening. Which we promptly ignored. Mum took to the jetset life with gusto, soaking up history and cultures, and traveling around the world into her 70s. On one notable occasion, and despite family misgivings, mum set off to Bangkok, by herself, just after 9/11 – aged 67. She was on her way to visit Ian and Cally in London, and nothing was going to stop her from doing that.

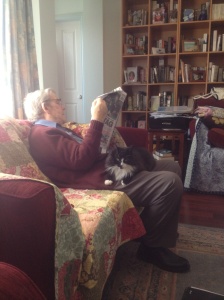

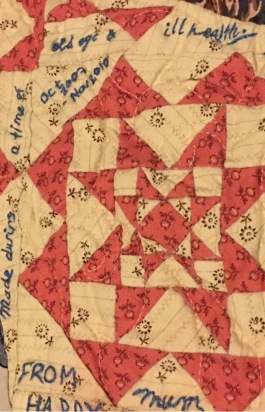

One of her greatest delights was creating things for others. After knitting her first jumper at age 11, the knitting needles hardly ever stopped. Look at any family photo from the 60s through to the 80s, and you’ll inevitably see kids sporting mum’s handmade knits. She was a prolific letter-writer too. Seeing her beautiful handwriting on a newly arrived envelope when you were far from home, was certain to lift the spirits – with family news, photos and mum’s life advice. In the 1990s, mum discovered patchwork quilting after a visit to an Amish Village in the USA. She created over 100 exquisite quilts, that are now our treasured heirlooms.

Close-up of text on the birthday quilt “Made during a time of old age and ill-health” Oct 2007-Nov 2010 “From Mum”

Mum didn’t just create tangible things like jumpers, letters and quilts, she also created intangibles – memories, moments, merriment – especially around celebrations of birthdays, Easter, and Christmas. She truly cared about people, and she enjoyed having a bit of fun too! She loved movies and music, and would sing or dance at the drop of a hat.

“Life is to be lived” she said, “to be enjoyed right to the end. Make the most of every moment.”

Coming from good Irish stock, Mum had a fine sense of the absurd. When Tony Abbott announced that he was bringing back Knights and Dames, mum’s planned morning tea morphed into a Royal Tea Party and she crowned herself Lady Muck of …… Some years before, she came to my New York–themed fancy dress party in QLD when I was about to leave for America. There was King Kong, Crocodile Dundee, several movie stars, and as guest of honour I was Madonna. Much to my embarrassment, the guest-of-honour’s mother turned up as a New York bag lady. Oh how she laughed remembering that story recently! Going back even further, when we as kids would ask how old she would be on an upcoming birthday, it would always be 29. Or 28. Or 25.

When mum first let me know a few years ago that she wanted me to give the eulogy at her funeral, I wondered if there was anything particular she wanted me to say.

Mum simply said: “Don’t sugarcoat it; just tell it like it is”.

Me: “OK….. so you don’t want me to say you were perfect?”

Mum, after a moment’s pause: “Hmmm, well, let’s say 99% perfect”

I asked what she was most proud of achieving in her very full life. This time without hesitation, she said

“My family. I feel very, very fortunate with my children. I have a very blessed life. And I love my grandchildren to bits. There’s not a one of them – kids or grandkids – that you wouldn’t be really glad to know. So I am twice blessed.”

Always fiercely independent, after succumbing to side-effects of treatment for multiple myeloma, mum had to let go, to allow her children to arrange her affairs, chauffeur her, take her to appointments, feed and look after her, as she had done singlehandedly for all of us so many years ago. What she didn’t seem to understand was that far from being a burden, doing these things for her was a privilege and an honour. Looking after each other – well you taught us that mum, that is what families are for.

Despite being in constant pain, mum accepted her lot, remaining positive and curious about the world, right to the end. She was anxious about one thing though. Late last year, when Christmas was coming up, followed soon after by several family birthdays, she said:

“I’m looking forward to Christmas so much, seeing everyone together again. It’s extra special this year as I wasn’t meant to be here for this one. I just don’t want to die on anyone’s birthday.”

Well, mum, you successfully navigated that minefield. Your death was the way you wanted it, peaceful, quick and not coinciding with a family birthday. You were ready to go, even if we weren’t ready for you to leave. We will be reminded of you every day by the simple things you always loved: a Richmond scarf, a cake stall, a flower garden, an old movie, a cup of tea with sympathy.

Personally, I will treasure the times we spent together recently, especially our last day – when you laughed over taking selfies. How many other 82 year olds have an iPhone, I ask you?

Mum, I will never forget that it was you who inspired me to reach for the stars, you who put that first precious sprinkle of stardust into each of your children’s hands, so that we too could aspire to be people who make things happen.

Judith Mary Martin, Judy, Mum, Granny

What an extraordinary life you lived, a life that touched so many

Now, you are, without doubt, forever 29 years old

and 99% perfect

The text below is the poem read out at mum’s burial, by Cathy Martin

“Remember me” David Harkins 1981

Do not shed tears when I have gone but smile instead because I have lived. Do not shut your eyes and pray to God that I’ll come back but open your eyes and see all that I have left behind. I know your heart will be empty because you cannot see me but still I want you to be full of the love we shared.

You can turn your back on tomorrow and live only for yesterday or you can be happy for tomorrow because of what happened between us yesterday. You can remember me and grieve that I have gone or you can cherish my memory and let it live on. You can cry and lose yourself, become distraught and turn your back on the world or you can do what I want – smile, wipe away the tears, learn to love again and go on.